Biography

“长的是磨难,短的是人生” --《公寓生活记趣》

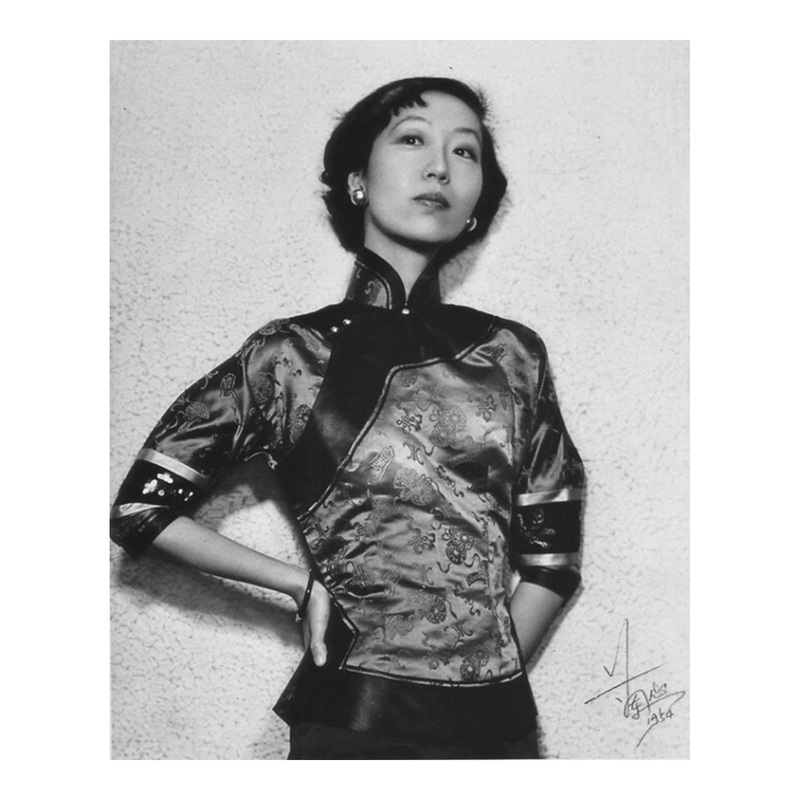

Eileen Chang 张愛玲 (Zhang Ailing, 1920–1995) is one of the most influential female Chinese writers in the 20th century. C. T. Hsia claimed that she was “the best and most important writer in Chinese today” (p. 389). Living through turbulent times from the late imperial China to the Republic of China and spanning across Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Los Angeles, her life was, much like her works, both romantic and desolate. Eileen Chang was born into a declining aristocratic family in Shanghai in 1920 and she was named Zhang Ying 张瑛. Her great-grandfather was Li Hongzhang 李鸿章 (1823-1901), the eminent late-Qing official; and her grandfather was Zhang Peilun 张佩纶 (1848-1903), a government official and the foremost member of the so-called Purist Party (清流派). However, her father, Zhang Zhiyi 张志沂 (1896-1953), although deeply rooted in Chinese classical literature, was addicted to opium and women. Her mother, Huang Yifan 黄逸梵 (1896-1957), partly educated in England, was a new modern woman of cosmopolitan tastes, and admired all things European. When Eileen was only two, she left for the United Kingdom and stayed there for five years. Her parents’ unhappy marriage eventually ended in a divorce in 1930.

Amidst her parents’ conflicts and an unhappy childhood, Eileen was sent to an old-style private school at the age of four and later enrolled in a Christian school in 1930. In 1939, she was offered scholarships and studied literature at the University of Hong Kong with an intention to proceed directly to Oxford. The outbreak of the Asia-Pacific War in 1941 forced her to return to Japanese-occupied Shanghai in 1942. Influenced by her father with a deep tradition in Chinese classical literature and her aunt with an overseas educational background, Eileen exhibited her eminent literary talent from a very early age.

She began writing her first story, Dream of Genius (天才梦), which is about a family tragedy, at the age of seven, and published her first work, The Unfortunate Her (不幸的她), in her school magazine, at the age of 12. These earliest sad stories seem to be a reflection of Eileen’s unhappy childhood and “foreshadow the maudlin tone of her writings decades on” (Louie, 2012, p.4).

The years in occupied Shanghai have been considered the best time for Eileen. In 1943 when she was 23, Eileen published her first “famous” novella, Aloeswood Incense: The First Brazier (沉香屑ˑ第一炉香) that brought her to the public’s attention. In the following years, she published a series of her most classic works, including The Golden Cangue (金锁記), Love in a Fallen City (傾城之恋), and Red Rose, White Rose (红玫瑰和白玫瑰). The success of these novellas soon made her a celebrity in the Shanghai literary circle of the time.

In 1944, Eileen Chang met and married Hu Lancheng 胡兰成 (1906-1981), a cultured literatus and a controversial political figure who served in the Japanese puppet government. They wrote “May the years be quiet and peaceful” (愿使岁月静好,现世安稳) in their marriage certificate. However, the marriage only lasted for three years; Hu’s continued womanizing and romantic involvement with other women caused a divorce in 1947.

Eileen’s life became difficult and she felt unwelcome in Communist China after 1949, as a wife of a Japanese collaborator and due to her insistence on being “apolitical” in the social change. In 1952, she went back to Hong Kong, where she worked for the United States Information Services, and wrote two novels that have been considered anti-Communist propaganda, The Rice Sprout Song (秧歌) and Naked Earth (赤地之恋).

Three years later in 1955, Eileen immigrated to the United States and endured a distressing time financially. In 1956, she remarried Ferdinand Reyher (1891-1967), an American screenwriter. Apart from a short spell in Taiwan from 1960 to 1962, Eileen had remained with Ferdinand until he passed away in 1967. In her last decades and the second-half of her “American” life, Eileen Chang remained single and became ever more reclusive. In addition to taking some short-term research positions at Universities such as the University of California, Berkeley, Eileen’s major work included a translation of The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai (海上花列传, 1894) and some research on the novel, Dreams of the Red Chamber (红楼梦). Eileen Chang was found dead in her Los Angeles apartment on September 8th, 1995. Her two autobiographical novels written in the 1970s, Little Reunion (小团圆) and The Book of Change, were published posthumously in 2009 and 2010.

Eileen’s works involve novels, essays, scripts, and translations. She is deservedly famed for her novels and essays. Her work, The Golden Cangue (金锁記) has been commended as the best novella of Chinese literature (Xia, 1979). Eileen’s novels depict a series of female characters, in particular, middle-class women in the two cosmopolitan and exciting cities, Shanghai and Hong Kong. The stories follow their choices of love and desires for money and power in a male-dominated society and during turbulent wartime in the 1940s and 1950s.

Unlike the majority of contemporary writers who looked at the grand picture and were obsessed with national salvation or revolution, Eileen Chang concentrated on personal stories and the mundane matters that affect human relationships in the midst of dramatic social upheavals taking place. Her novels describe the misfortune that befell women and warped families of urban China during a time of social dislocation, and “weave an intricate relationship between the literary, the mundane, and gender” (Louie, 2012, p.8). With subtle details of “romancing the ordinary” and merciless examination of human weakness and self-interest, the lingering mood of melancholy and desolation resonating throughout her works vehemently impacts readers, and the feeling of desolation has been successfully developed into “an aesthetics for the commercial consumption of the petty bourgeois” (Zou, 2011). Her essays document her innermost thoughts and feelings about her private life and the world around her.

Eileen Chang is unique in modern Chinese literature in her honesty as a sensitive observer and deliberate recorder of the Chinese urban life around her in a changing time. One thing is sure, as pointed by Kam Louie, “this singular voice will continue to appeal to readers who will no doubt respond to it in their own individual ways” (Louie, 2012, p.13). Eileen Chang has influenced many creative writers in the mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Many of her works continue to be adapted for the stage, TV series, and films.

References:

Hsia, C.T. (1961). A history of modern Chinese fiction, 1917-1957. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Huang, N. (2005). Introduction. In Chang, E.; Jones, A.F. (Trans.) Written on water (pp. xii). New York: Columbia University Press.

Louie, K. (2012). Introduction: Eileen Chang: A life of conflicting cultures in China and America. In Louie, K. (Eds.) Romancing languages, cultures and genres (pp.1-13). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Xia, ZQ. (1979). Zhang Ailing. In A history of modern Chinese fiction (pp. 385-372). Hong Kong: Union Press Ltd.

Zou, L. (2011). The commercialization of emotions in Zhang Ailing’s fiction.” The Journal of Asian Studies 70 (1): 29-51