Artisans and Workers

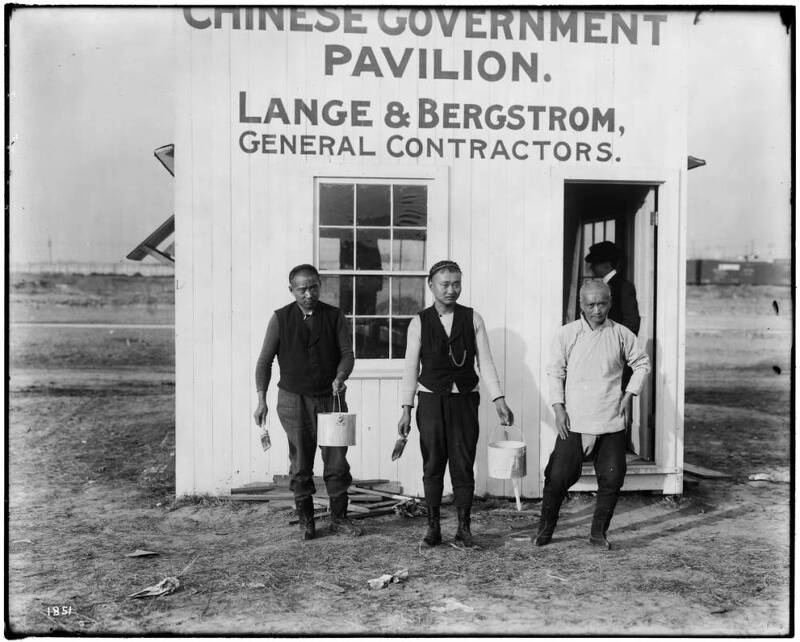

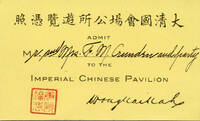

Over 200 skilled woodworkers, painters, and artisans traveled from China to St. Louis to construct the elaborate Chinese Pavilion at the World’s Fair.

The first group of 23 artisans, accompanying Vice Commissioner Wong Kai Kah, were assigned the task of building the Chinese Pavilion and Village. The carpenters, sculptors, and woodworkers lived with the Wong family at their home, and used the cellar as a workroom. An additional 194 artisans arrived in the next months to continue the work.

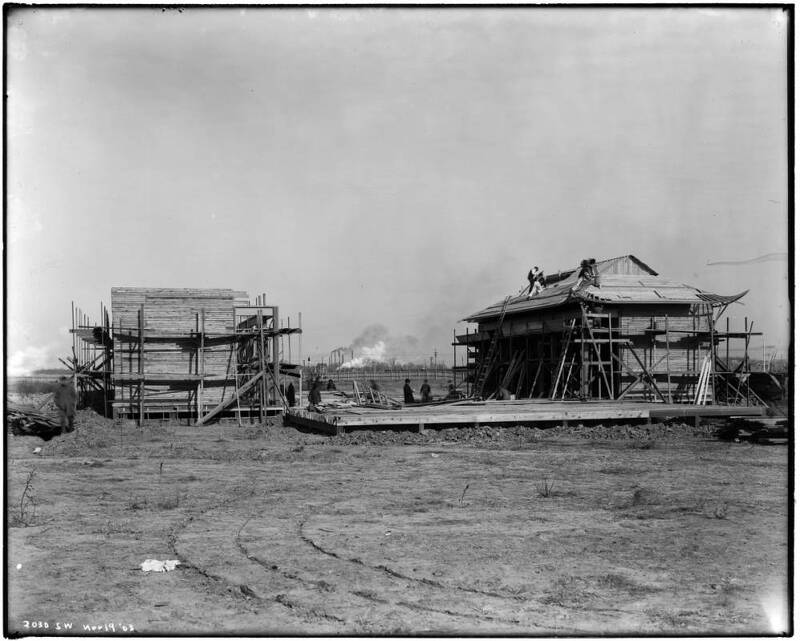

Thousands of laborers transformed the land of Forest Park into the complex grounds of the World’s Fair.

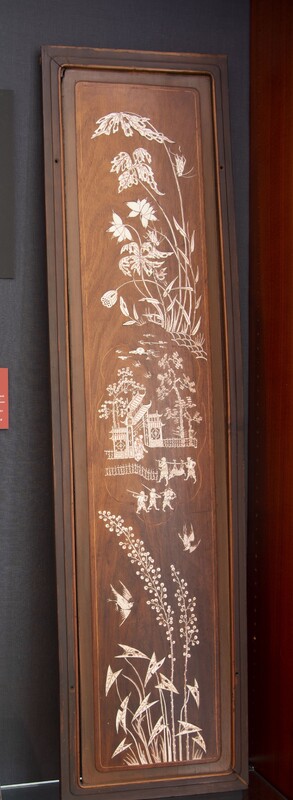

American workmen started the framing for the Chinese Pavilion, but artisans from China constructed most of the building, adding details to the elaborate structure using traditional methods.

Harsh Controls

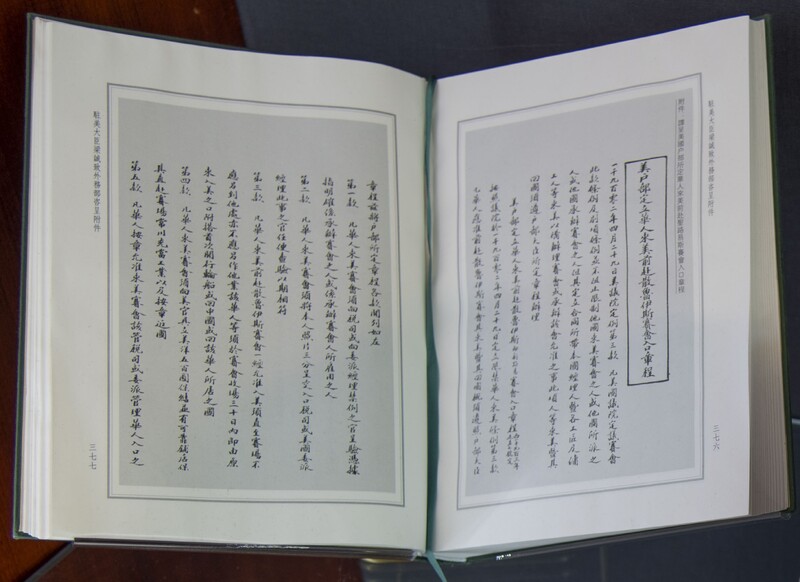

When workers arrived from China, they faced harsh controls by the U.S. Immigration office: each was photographed and registered, and ordered to stay close to their housing. Once in St. Louis they were required to report to the police office daily. Failing to show up within 48 hours meant that the worker would be considered a fugitive, facing arrest and deportation.

The draconian measures faced by workers arriving from China are documented in detail by the Chinese archives. They are a sad chapter of American history known as the era of Chinese exclusion.

Life in St. Louis

The Fair aimed to be a showcase of modern society and innovation, and at the same time, perpetuated racial exclusion in its parades and displays.

Artisans and workers from China had little-to-no opportunity to interact with Chinese immigrants who lived just six miles away in St. Louis’ Chinatown – Hop Alley.

Starting with the 1857 arrival of Alla Lee, a tea shop merchant and Ningbo native, the neighborhood nicknamed “Hop Alley” began to grow. By 1900, there were about 300 Chinese calling St. Louis home near Market and 7th Street.

Although no laws prevented people of color from purchasing a ticket, the long-standing de facto segregation of St. Louis makes it unlikely that Chinese residents attended the Fair.