Wong Kai Kah and Madame Wong

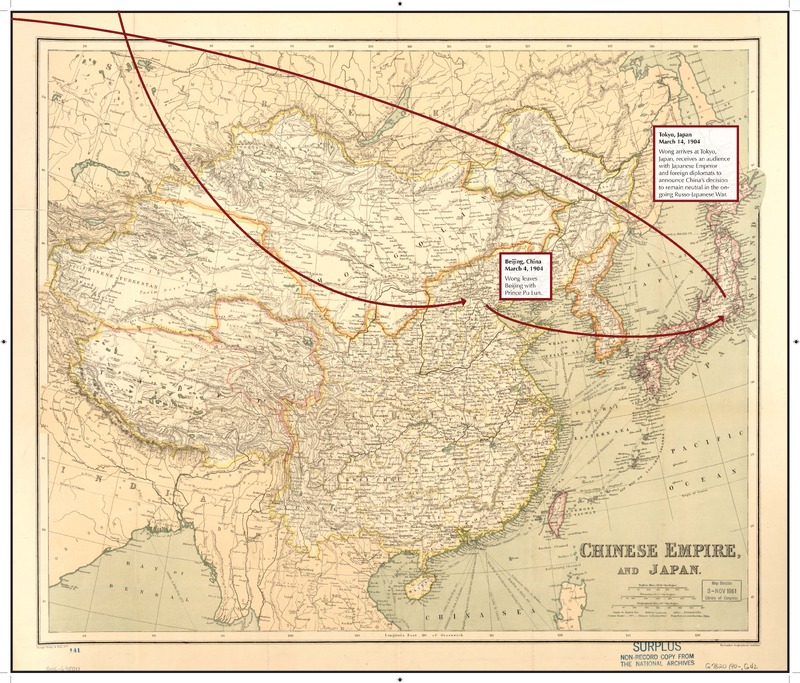

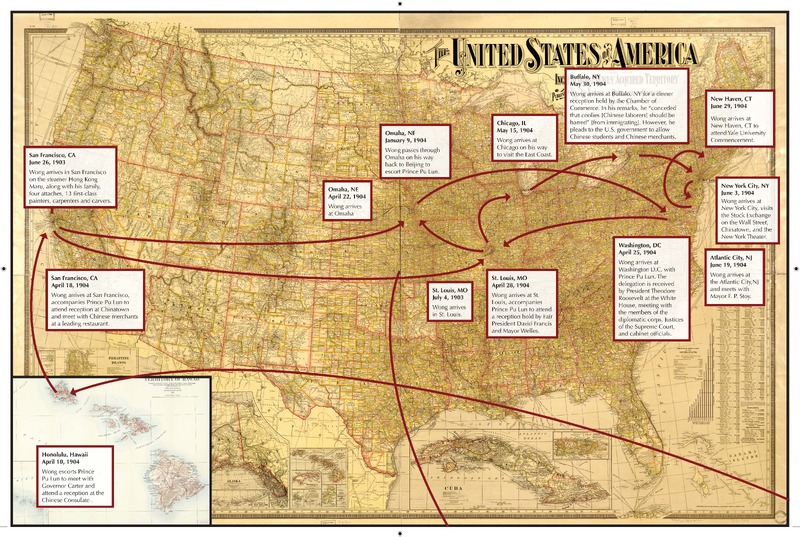

Wong Kai Kah's appointment as Imperial Vice Commissioner of the Chinese delegation marked a highlight in his diplomatic career. Having lived and studied in the U.S. from ages 12 – 20, Wong was an ideal diplomat to represent China’s concerns on a global stage.

As Emissary to the United States in 1902, Wong helped negotiate China’s terms of participation at the World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Biography

Wong Kai Kah

Born: 1860, China

Died: 1906, Japan

Education: Traveled to U.S. as part of the Chinese Educational Mission, 1872. Lived with a sponsor family in Hartford, Connecticut. Attended middle and high school, then studied at Yale University through 1881.

In 1905 Wong Kai Kah represented China in the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth, which ended the Russo-Japanese War.

Madame Wong

Limited documents about her life are available, and her birth and death dates are unknown.

Born in Japan, and adopted by a Chinese family, Madame Wong's ethnicity was kept a closely-guarded family secret. Although Madame Wong herself had bound feet, she refused to bind that of her daughters.

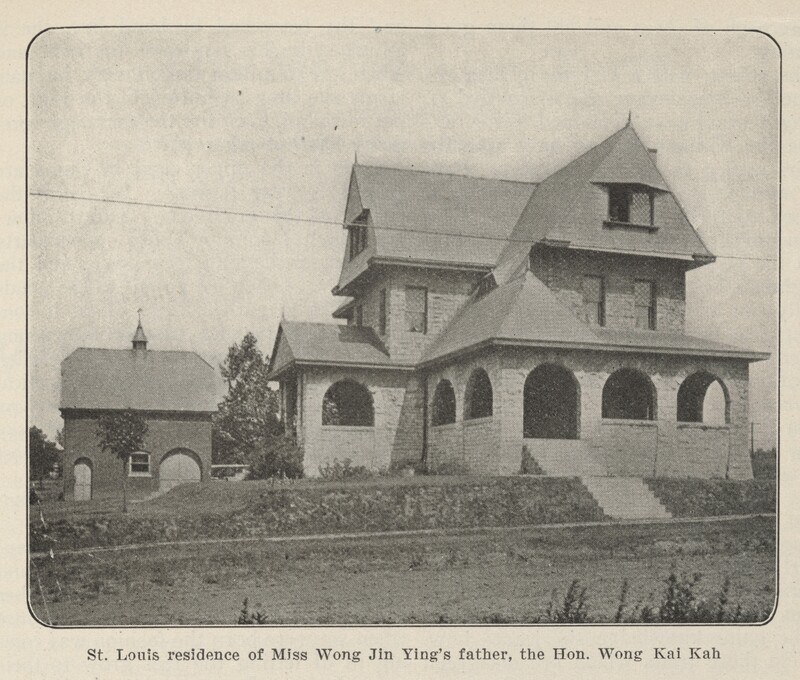

St. Louis

In 1903, a few months prior to the opening of the Fair the entire family moved to the United States. Mr. and Mrs. Wong, their three boys and two girls, accompanied by one secretary and two servants, traveled together to their new home in St. Louis on Goodfellow Avenue.

As of 2024, the building at 1385 Goodfellow Avenue still stands in, now serving as the Emmanuel Missionary Baptist Church.

The Wongs, were in general, well-received in St. Louis high-society. Yet, neither Wong’s exceptional command of the English language nor his knowledge of American culture and politics could shield him from being perceived as a perpetual foreigner---viewed as an outsider, regardless of accomplishments or cross-cultural competence.

Exclusion

Starting with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a series of federal U.S. laws banned Chinese laborers from immigrating, and it made it illegal for Chinese nationals already in America to become naturalized citizens. Chinese immigrants had to register with immigration authorities and carry a Certificate of Residence with them, without which they could face deportation. The Exclusion laws not only impacted Chinese artisans here for the Fair but also the Chinese communities living in the heartland of America.

Wong spoke and wrote frequently against this policy.

Feminine Roles

While Wong Kai Kah worked with his U.S. counterparts at the Fair, Madame Wong met with the St. Louis Society and personally oversaw all arrangements for the interior decoration of the Chinese Pavilion in St. Louis.

In newspaper interviews, Madame Wong expressed her desire to share Western ideas of femininity with Chinese women, hopeful they would travel, see the world, study different subjects, and generally not be confined to the home.

Yet American media mainly focused on sensationalism and exoticism. Articles such as “A Poetical Trousseau” (Olneyville Times), “Ms. Wong’s Pretty Clothes” (Savannah Morning News), and “Wonderful Gowns” (Times Dispatch), meticulously described every stitch, ornament, and detail of the 300 embroidered gowns Madame Wong brought to St. Louis.