Facing Realities

Imperialism

By the start of the 1900s St. Louis was a mosaic of people. Nearly one third of its population were foreign born, and many more were first-generation Americans. European immigrants from Germany, Ireland, and Italy, and African American migrants from the south, made the booming city their new home. City officials kept a close watch on these newcomers—permanent and transient, and guarded the physical and cultural boundaries separating immigrants from white residents.

In many ways, the World’s Fair in 1904 afforded St. Louis an opportunity to imagine the future of the racial order for the city and the nation. It represented a polite form of U.S. imperialism, accompanied by the vulgar racism that targeted non-white indigenous and minority groups.

Facing difficult history

While the 1904 World’s Fair is often recalled with nostalgia for its grand buildings or its quirky Olympic events, it is essential to acknowledge the Fair’s darker side, rooted in racism and imperialism.

Much of the world was brought to St. Louis by the Fair’s organizers. Thousands of indigenous peoples were imported and put on display in villages designed to recreate their native habitats, all to dramatize man’s hierarchical racial order. Sensational advertisements—“Grand March of the Barbarians,” “Types of Mankind from Many Continents in the Stadium,” —sought to entertain fairgoers, while proving and promoting the superiority of the white race and of western civilization.

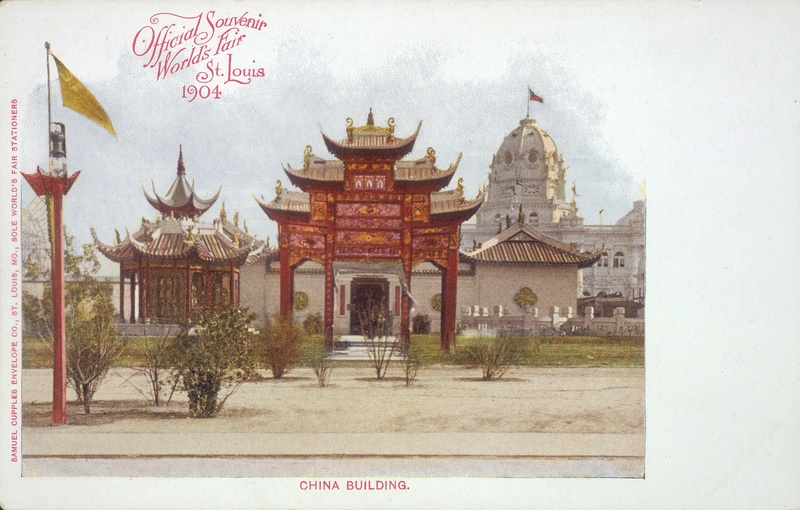

China’s exhibits were divided and found throughout various palaces and zones, not just in its official and elaborate Chinese Pavilion. So how then did Fair organizers exhibit the Chinese civilization and the Chinese people on the universal evolutionary scale? Not “barbaric,” as China demonstrated a rather long and splendid history, sophisticated culture, and material wealth. China’s products were favorably compared to those of the industrial West, and noted as having a long and rich tradition, yet locked in its own ancient backwardness.

In the years after the Fair, most histories were written from the perspective of white fairgoers and organizers. Instead, the research in this exhibit tells the stories of those invited to St. Louis from China.

“When we started looking for our ancestors' traces, footprints, and stories in St. Louis. It was quite difficult because we were not included as part of the local history, which is why we joined the research team. As Chinese Americans living in St. Louis, we hope to uncover the veil of the past and continue honoring and celebrating our legacy here.”

— Kaiyang Ma (Wydown Middle School), Ayden Tian Huang (Ladue Middle School), Yiding M. Tang (John Burroughs School)