Cartoon as Artifact: The Evolution of the American Gag

curated by Tommy Attwood

What can gag cartoons reveal about the societies that produce and circulate them? Gag cartoons capture moments in time, often expressing prevailing national anxieties and political opinions. Investigating the development of the gag cartoon from the Gilded Age to present day, a story unfolds about the evolution of American humor, politics, and print culture. The gag cartoon becomes a valuable historical artifact, providing unique insight into societal nuances over time.

Form and Function of the Gag Cartoon

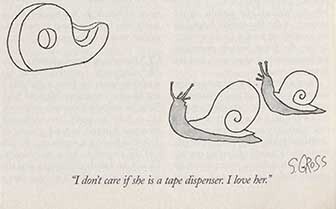

When we think of a gag cartoon, we often think of the classic New Yorker cartoon: a simple grayscale image with a quick caption. This form was born from a number of more complex, harder-to-define versions of the gag, which appeared in late-nineteenth century humor magazines like Puck, Judge, and Life. The function of the gag has remained a consistent component of its definition; gags tend to fall within one of three categories: jokes, political opinions, or both.

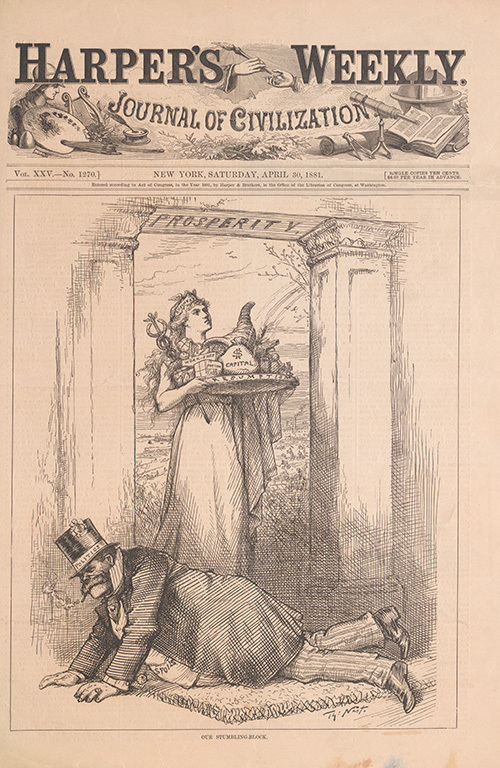

The Gilded Age and Thomas Nast

The post Civil-War decades saw an influx of elaborately-drawn political cartoons. Detailed engravings were affordable to produce at the time, so magazines hired cartoonists like Thomas Nast (1940-1902), a formative figure of Gilded Age political cartooning. Nast is credited with the popularization of a number of classic American symbols, including Uncle Sam, the Republican Elephant/Democratic Donkey, and the modern Santa Claus. His cartoons attacked Tammany Hall and contributed to the defeat of Horace Greeley in the 1872 presidential campaign. His career exemplifies the cartoon’s powerful ability to sway public opinion.

This colorful, full-spread in Puck embodies the early American gag cartoon. The art is its most striking quality, while the concept requires a bit of interpreting. In other words, form is valued over function.

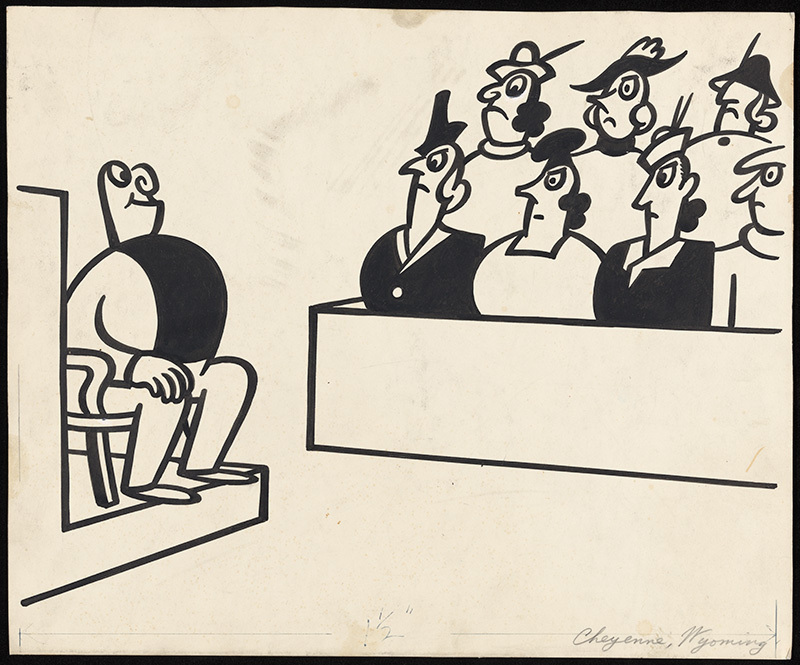

Cartoonist Otto Soglow’s work illustrates a massive visual shift in American cartooning, a shift that was largely driven by technology. In the early twentieth century, photography outshone elaborate artwork in magazines. Cartoons transitioned to a simpler visual form that was more practical and inexpensive for magazines to publish.

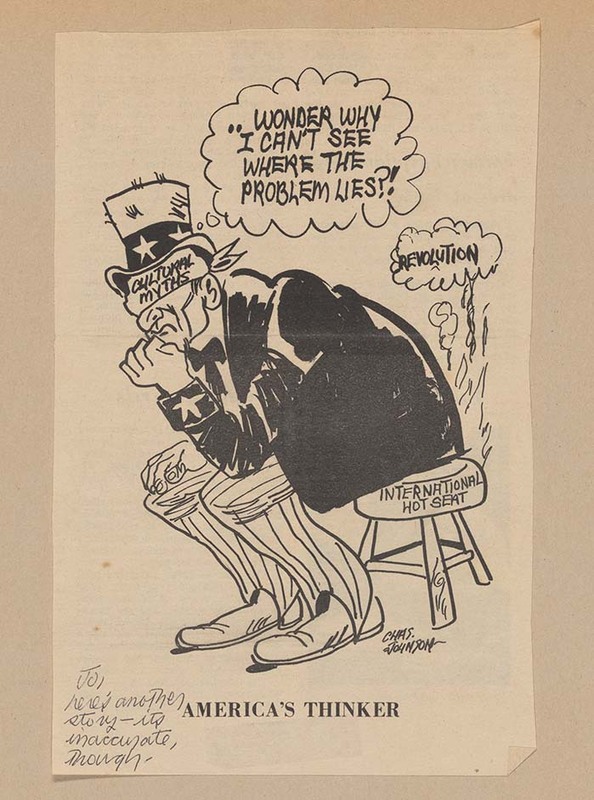

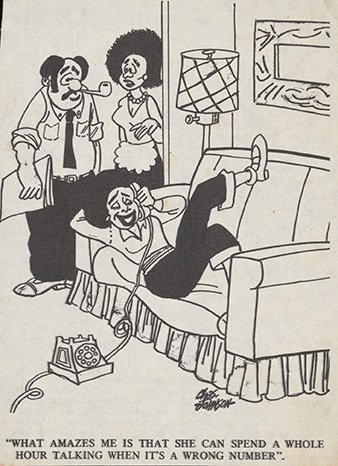

Charles Johnson’s cartoons depict and celebrate Black life in America. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Johnson used cartoons to confront white-supremacy, segregation, and police brutality. He gave a voice to Black Americans in a field dominated by white cartoonists and audiences. Johnson has criticized the lack of representation of cartoonists of color in The New Yorker.

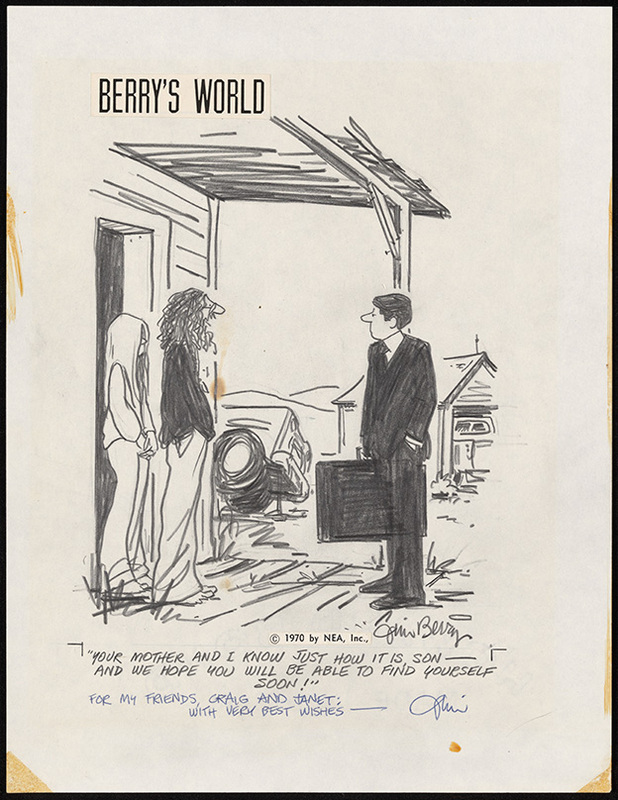

Jim Berry’s cartoon humorously captures a moment in time: the spirit of the 70s.

Under the direction of co-founder Harold Ross, The New Yorker streamlined the gag cartoon. Ross valued simplicity in dialogue, clear identification of the speaker, and integrity in the relationship between the image and text. The art did not need to be highly skilled or rendered; it needed to simply and effectively communicate the idea. Today’s New Yorker cartoons continue to follow this model.